THE STATE APPARATUS

The government of the lagoon people began as a revolt against their Byzantine rulers and developed as a pact between the people and the leader they elected. In exchange for granting him absolute power, he protected them from invaders and kept them safe at sea. If he failed them, they replaced him. Wealth and power dramatically transformed that paradigm into the rule of a hereditary oligarchy deployed in interlocking committees and councils, part of a precisely calibrated system of checks and balances designed to maintain itself. That was its brilliance and its undoing.

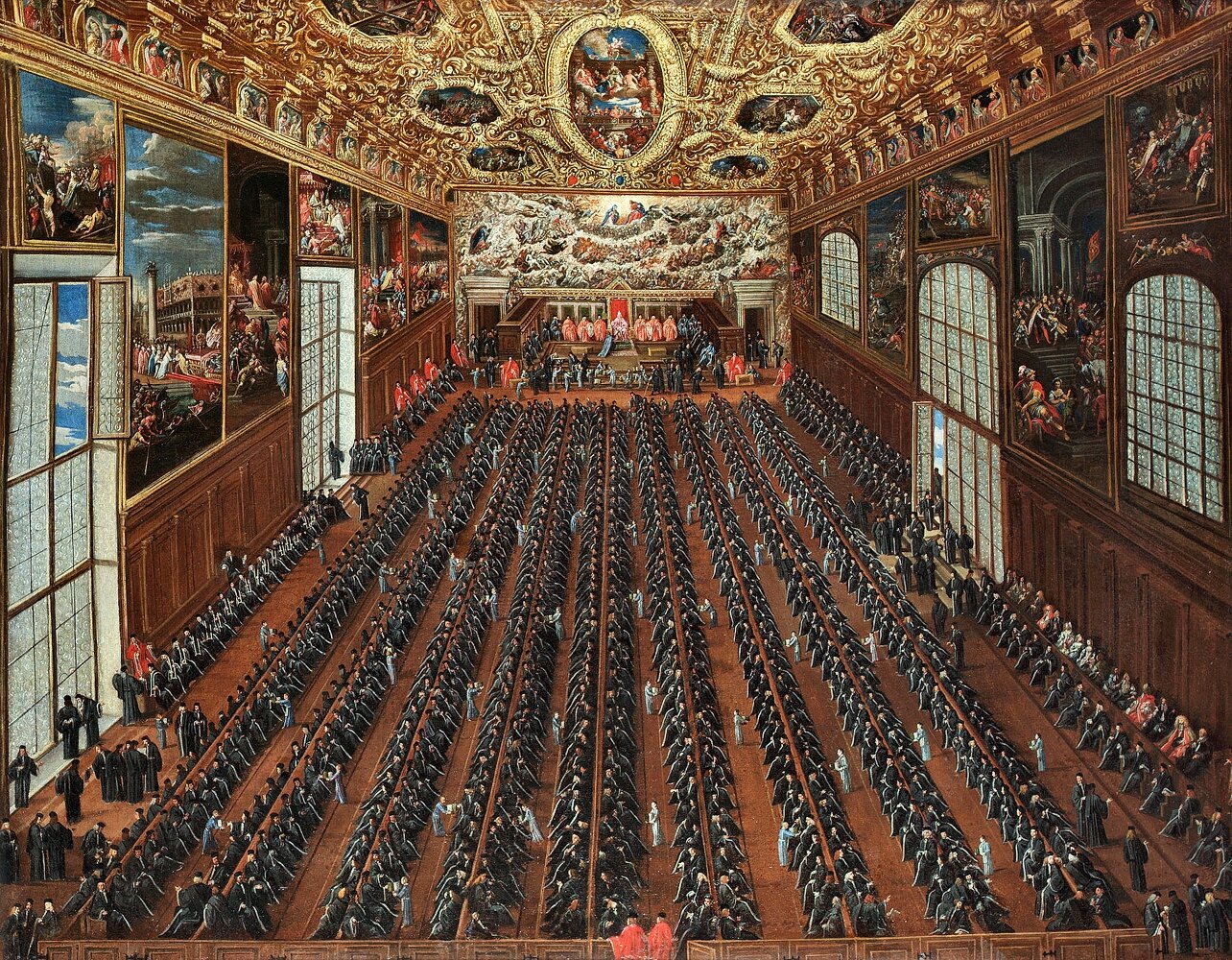

The Great Council was created as part of the government reforms of 1172, which also created a system for electing the doge. All the nobles were part of the Great Council, and by 1297 the Great Council and the nobility were synonymous. Any role the arengo, the old popular assembly, had played in governing was eliminated. In the early 14th century “the Great Council was the sovereign organ of government and the keystone of the system.” (Crouzet-Pavan)

The sovereignty of the Great Council didn’t last long. As it spun off councils and committees it created centers of power that held it, each other, and the doge, in check.

The main councils were:

THE COUNCIL OF FORTY (Quarantia)— Established as part of the constitutional reforms of 1179, the quarantia was the highest court, consisting of 40 members elected from the Great Council. The three heads of the Forty were part of the Doge’s Council, the Signoria. During the 15th century the Forty was divided into 3 separate Councils: the Quarantia Criminal (criminal law); the Quarantia Civil Vecchia (for civil actions within Venice) and the Quarantia Civil Nuovo (for civil actions within the Republic’s mainland territories).

THE SENATE, which began as a group of advisors, was expanded to sixty members (later 120) and formed the highest legislative body, although the legislation they debated often originated elsewhere.

THE SIGNORIA was the highest level committee, consisting of the Doge, his six counselors, and the three heads of The 40. The doge was not allowed to choose his own advisors according to his inclinations. They were elected by the Great Council, they could veto the doge, and he was bound by his oath to submit to them. The shroud of Marino Faliero painted over his portrait in the Great Council Chamber served as memento mori to every subsequent doge that the axe was never far.

The terms of all committee assignments, highest to lowest, were strictly limited, from three to twenty-four months, and consecutive terms were not allowed (in fact, a noble needed to be off a committee twice as long as he he had been on before he could be reelected to the same committee).

“One visitor, Philippe de Voisins, wrote, ‘the doge holds the said duchy for his lifetime, if they find nothing for which he must be undone,’ adding ‘he can do nothing out of the presence of his counselors.’ ... The person who is shown in the spectacle of his full power is in fact supervised and controlled by councils who have the power to depose him.”

THE DOGE

The complex system of electing the Doge began with the constitutional reforms of 1172 and was completed in 1296. The process mingled straightforward voting in committees with lotteries to determine who would be on the committees. Chance — the randomness of the lottery — was seen as a foil to cabals and conspiracies. By the 14th century no noble elected doge was allowed to refuse the office, abdicate, or otherwise resign.

The doge swore an oath of office, which grew over time. Upon the death of each successive doge, his actions were examined. If, post mortem, he was found guilty of any malfeasance or corruption, his family got the bill; another measure designed to keep him in line. By the last doge (1797) the oath was 301 pages of rules and restrictions. The doge was constantly under strict surveillance: he had to wait for other officials to be present before opening dispatches from foreign powers; he was not allowed to possess any property in a foreign land, nor hold private discussions.

Progressively the doge became as much a figurehead as the golden statue of Justice on the prow of the Bucintoro, his golden boat.

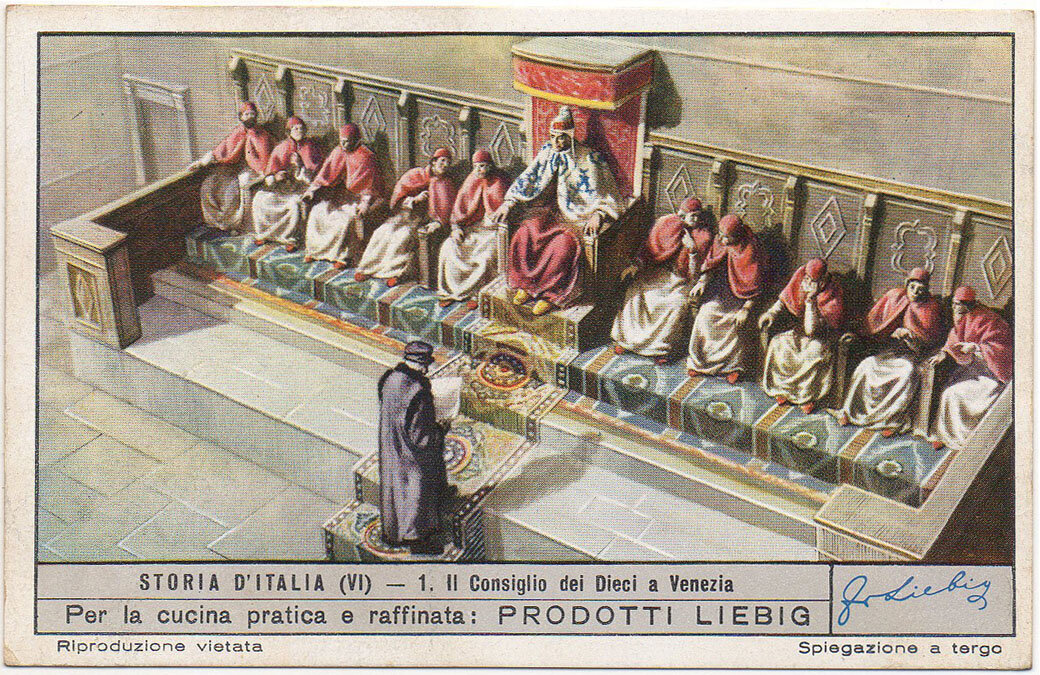

THE COUNCIL OF TEN

“The new aristocracy [which] triumphed [over Bajamonte Tiepolo’s conspiracy in 1310] proceeded to follow unimpeded the law of its growth. Externally the government of the city was crystallized... A full police system was developed—the patrols for the streets, the guards for the canals, the piazza, and the doge’s palace. But freedom was not in the nature of the new aristocracy; its essence was opposed to liberty, and so it was doomed in turn to submit to itself as its own most tyrannous master. The danger it had just escaped was so great that, for its own immediate safety, it had recourse to a dictator. But following the inherent bent in the Venetian political constitution, that dictator was not an individual but a committee. The Council of Ten... became the lord, the Signore, the tyrant of Venice. It was no concrete despotism, but the very essence of tyranny. Evasive and pervasive, this dark, inscrutable body ruled Venice with a rod of iron... It is the Ten which determined the internal aspect of Venice for the remainder of her existence.”

“Without indulging in sensationalism, it is fair to say that the power of the Ten reached a peak in the fifteen and sixteenth centuries... It created the famous Inquisitors against the Propagation of Secrets, the body that preceded the institution of the State Inquisitors. On several occasions the Great Council passed statues to settle difficulties and controversies and reassure those who were alarmed by the Ten’s growing hold over public life. The momentum was irreversible, however, and during the course of the fifteenth century Venetian power tended to function in increasing secrecy. The mechanisms of decision were gradually remodeled, and the Council of Ten played a fundamental role in the new political landscape.”

The government power structure of the Venetian Republic is often visualized as a pyramid (as in the diagram on the right).

This image fails to take into account that after the 12th c. the power of the doge was increasingly limited, his prerogatives taken away, and his freedom of action curtailed until he became a figurehead with no independent power at all.

The “pyramid” also fails to take into account the fact that membership on the councils was interchangeable, a revolving door of members drawn from the same pool cycling through interlocking committees and councils.

A far more accurate representation would look something like the intricate cogs and gears of a clock, with the Council of Ten as the mainspring, simultaneously driving and restraining the operations of the mechanism, its smooth operation regularly interrupted by random events.